Four years ago on my birthday I gave my two weeks’ notice at the animal shelter where I worked. Quitting felt like defeat, guilt, and failure, wrapped in a heavy, wet blanket of numbed out exhaustion. But it was still a good birthday present to myself. I needed out.

I knew I was in trouble months earlier when I started crying as I drove into work in the mornings. Towards the end of my time at the shelter, I began to move through the morning routine in a sad trance. Tears would silently roll as I went about filling food bowls, walking dogs out to the yards for their morning bathroom break, and putting meds together.

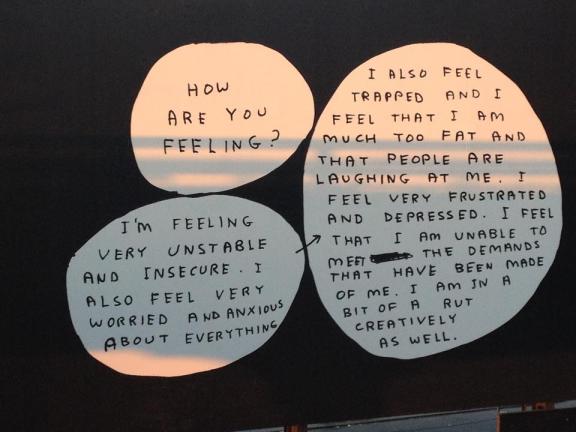

I was sad. I was really angry. I was exhausted, mentally and physically, down to my core. And I knew I wasn’t helping the dogs anymore. I was in such bad condition that I knew I wasn’t able to do my job effectively.

I was completely burned out.

So I left. I felt guilty that I was leaving my fellow co-workers behind in the trenches to do the work I couldn’t do anymore. I felt sick at the thought of abandoning the dogs that were still waiting for homes. But I knew I had to go.

It took months to start feeling better. Actually, if I’m being honest, I was so busted that I didn’t feel like myself for more than a year after I quit. No joke.

These days I’m still involved in animal sheltering, but from a distance. In addition to dog walking part-time, I do some writing for an animal welfare non-profit. So I’m still in the loop. And in my work I see a lot of advice geared towards shelter and rescue workers instructing them to be more positive, provide better customer service, to be less judgmental, more compassionate, and more understanding when working with the public.

It’s a reminder that in order to help the animals, we must also help people. We can’t hate people if we want to help animals. When I hear this advice I always nod in agreement. It’s the truth.

But a little voice – a voice from four years ago – always pipes up too: Remember, that’s easier said than done. Who is teaching shelter workers the skills they need to stay positive and open-minded with the public? Where is the compassion for underpaid, overworked shelter workers?

Because the truth is, the work is brutal. Caregiving is hard. All helping professionals struggle: nurses, firefighters, social workers, etc.

The nature of the job is a Catch-22. In order to do these kinds of helping jobs, you have to be empathic. But if you’re emphatic to a traumatized population, then you’re exposed to their suffering. The demands for your empathy are constant and often overwhelming, which leads to high residual stress levels. When this isn’t dealt with, it leads directly to Compassion Fatigue (CF). And that impairs your ability to be compassionate, positive, and helpful to the very population you serve.

Side note: there is one critical difference between all the other helping professions and shelter workers. We’re the only ones that sometimes have to kill those we are assigned to care for. As big as that is, let’s put euthanasia aside for the moment, because you don’t have to be a euthanasia tech in order to experience Compassion Fatigue (though it does correlate with high turnover rates).

What is Compassion Fatigue? It’s exhaustion due to the stress and demand of being empathetic and helpful to those that are suffering.

And this is what it looks like from the book To Weep For a Stranger, “When caregivers focus on others without practicing authentic, on-going self-care, destructive behaviors can surface. Apathy, isolation, bottled up emotions, substance abuse, poor personal hygiene, and emotional outbursts head a long list of symptoms associated with the secondary stress known as compassion fatigue.”

Untreated, Compassion Fatigue leads to Burnout. But Burnout is different than Compassion Fatigue.

“Clinicians can experience burnout, but burnout can be experienced by anyone who works too hard, too long, or under too much stress without being exposed to trauma or trauma survivors, as is necessary in a CF assessment. Burnout pertains to the work environment, whereas CF pertains to the emotional involvement of extending empathy to trauma survivors.” From Resilience as a Protective Factor Against Compassion Fatigue in Trauma Therapists.

Once you’re in burnout, you’re not likely coming back. You hate your job at this point. But when you’re dealing with the symptoms of Compassion Fatigue you can, with help, come back from the brink. And, even more importantly, you can protect yourself against Compassion Fatigue through regular self-care and building resiliency.

Sadly self-care doesn’t come naturally to most of us working in shelters and rescues. For me, I knew in theory how to take care of myself, but when the going got really tough I just couldn’t manage to make self-care a priority. I was so tired that all I could do at the end of the day was eat ice cream and watch TV. Many of the people around me at work were also exhausted or numbed out. I think we were all waiting for a break in the relentlessness of our jobs to “catch up” on caring for ourselves. But the break never really comes. I didn’t know how to care for myself in a long distance race with no finish line. Or why it was so important.

The truth is that in order to do this work well – to care for animals and people – you need to be able to care for yourself first. Just having the technical skills to do the job isn’t enough. It’s not enough to know proper sanitation protocols or disease management. Or how to do skilled behavior evaluations. Or know how to handle, socialize, and enrich animals. Or how to speak with potential adopters and counsel them on choosing the right pet.

All of those are skills you need, of course. But you won’t be able to use any of those skills if you’re falling apart. Compassion Fatigue takes away your ability to do good work. Feeling negative emotions and not having the skills to cope with them impairs our ability to connect with other people, think creatively, problem solve, and work well with others.

So all the advice in the world, all the finger wagging, the training seminars, the shaming comments about shelter workers needing to stop saying “I hate people” – none of that is going help them do a better job. Not unless we address Compassion Fatigue and Burnout, since that’s one of the root causes of why they’re not being effective at their jobs.

So why isn’t addressing Compassion Fatigue as important a part of the job training as how to do an evaluation or talk to an adopter? Why isn’t this a priority at every organization?

No one ever said the words “compassion fatigue” to me when I took the job at the shelter. I didn’t understand that what I was initially experiencing wasn’t the same as burnout from a tough job with long hours. It didn’t happen right away, but when symptoms of Compassion Fatigue hit me, I was deeply affected. I felt like no matter how many hours were in a day, I could never give the dogs at the shelter the level of care that I knew they deserved and needed. I worked so hard. But it never felt like enough. No matter how much I did in a day, I rarely felt like I had succeeded. It wore me down.

Of course, there were adoptions. Glorious, wonderful, heart-filling adoptions. I can’t tell you how good it felt to send a dog home with their new family. It was joyous and hopeful and…for me, increasingly scary.

Dogs would come back, returned by the families that had adopted them. That’s part of the job. It was disappointing, but not devastating. But then I encountered a really bad stretch. Dogs that I had personally adopted out were coming back to us abused, neglected, and damaged. Not a lot of dogs. Just a handful. But when you find out that a dog you cared for and sent home with a family that you thought was OK was later found dead or comes back to you 20lbs lighter and covered in scars, it only has to happen a few times to shake you. I started jolting awake at night, sick from nightmares about the dogs that had suffered.

My favorite part of the job – adoptions – felt tainted.

I felt like I couldn’t really trust myself or others. How would I know when a family was lying to my face, as some clearly had? Despite my training and adoption counseling skills, I could never really know if I was sending a dog to an abusive, neglectful home. I had to be ok with that uncertainty, but I felt vulnerable and afraid instead. Which made me feel shut down and negative towards the public.

If you’re reading this now and thinking: You shouldn’t have gotten so hung up on the negative – studies show that the majority of adoptions work out. Or you can’t control everything and wait for the perfect home. Or always keep your eye on the big picture, rather than getting stuck on a small percentage of adoptions gone wrong. You’d be right.

But here’s what I know now, that I didn’t know prior to doing direct care for the dogs: the map is not the terrain.

You can give people the very best instructions, the most effective techniques, the most cutting edge tools and research – the maps– but they mean almost nothing when you’re dropped into the reality – the terrain – of being a caregiver in an animal shelter.

For example: A map can tell you the elevation of a mountain. But just reading the map while sitting on the couch isn’t the same as what you feel while navigating the terrain. Until you do it, you won’t know exactly when your leg muscles will start spasming as you try to scale that terrain.

The map tells you suggested questions to ask potential adopters. The terrain is filled with the bottled up pain of the dog you just euthanized minutes before meeting a potential adopter, the fear of repeating your past mistakes, and the confusion of being unsure if the person you’re talking to is a good home or not as you try to ask those questions. The map alone isn’t enough to help you get through the terrain.

If we actually want shelter staff to do a better job, to be more compassionate towards the public, to be more effective and to save more lives than we have to do more than give them a really good map filled with “how-to” instructions for how to technically do the job. We have to make self-care a priority so they can stay healthy enough to tackle this complicated emotional terrain.

I’m just going to stop for second to address those of you that are saying to yourself: There are plenty of shelter workers that are terrible. They hurt and abuse the animals in their care. They’re hateful to people. They don’t care about lowering euthanasia rates. Shelter workers ARE the problem.

I know that there are some truly awful shelter workers out there. There are also some amazing shelter workers out there that really don’t get bogged down by all the negative stuff and need little help navigating this difficult terrain. They’re the two ends of the spectrum. The really horrible and the really high functioning.

But the average shelter worker is just a regular person that falls somewhere in the middle. They’re trying (and sometimes failing) to do a good job. They love the animals. And they need compassion and resources in order to do a better job. They are exactly the same as the public and adopters in that regard. If our goal is to help the animals, we have to care for and help people – and that includes people who are shelter workers.

We can’t ask them to do better work without addressing the coping skills they’ll need in order to do a job that can be emotional hell. Let stop for a second and consider what we’re really asking shelter worker to do: We’re asking them to provide constant care for animals in need, some of whom are traumatized. To experience having little control in where those animals ultimately wind up. To feel the fear that things might go badly in an adoption and to let it go. To (sometimes) kill those they’ve cared for. To be vulnerable, to stay open, and to remain positive in the face of what scares and stresses them.

Not an easy terrain to navigate. American Buddhist nun, Pema Chodren, writes in her book The Places that Scare You, “When we practice generating compassion, we can expect to experience the fear of pain. Compassion practice is daring. It involves learning to relax and allow ourselves to move gently towards what scares us.”

Shelter and rescue workers – just like the rest of us – aren’t Buddhist nuns. But that’s essentially what we’re asking them to be: comfortable being vulnerable in their compassion. None of us – shelter workers to nuns – can do that without a lot of practice.

So what does help? Recent research shows that Resilience can protect against CF and burnout. Resilience is built through awareness and self-care. Self-care is when we commit to nurturing a life outside of work that can counterbalance the intensity of the job and the inevitable stress that comes along with it. When we take care of ourselves, we build the resilience we need to deal with the negative aspects of our job, as well as building job satisfaction. That helps us to feel positive and allows us to do our jobs better.

Self-care is about finding ways to restore a balance between the negative and the positive by cultivating aspects of our lives that support us when the going gets (and stays) tough. It’s about making a commitment to caring for yourself as deeply and seriously as you care for the animals. Because if you don’t, if you allow yourself to become mentally and physically run down, mired in negativity, sadness, and anger, then you can’t do your job all that well.

If you’re saying to yourself: “I don’t have time for self-care. The animals need me constantly!” I want you listen up:

Research shows that there is a correlation between ethical violations and Compassion Fatigue. Which means Compassion Fatigue can cause us to cause harm to others.

That means: YOU ARE ETHICALLY OBLIGATED TO TAKE CARE OF YOURSELF.

When we disregard our own needs in order to keep giving to others it’s not just bad for us, it’s unethical. So if you think that being a good caretaker means caring until you collapse you are wrong. In order to be a good caretaker, you must take care of yourself so that you can care for others properly. Otherwise, you have the potential to harm those that you are caring for.

Let me say this again: it is UNETHICAL TO NEGLECT SELF CARE. So it’s not indulgent to take care of yourself. It’s not a sign of weakness. It takes courage to commit to self-care. It’s the right thing to do. It’s not optional.

What does self-care even look like? It’s going to be personal for each one of us, but generally self-care and building resiliency looks like: setting boundaries, saying no, working less, exercising, eating well, going to therapy or a support group, cultivating friendships, monitoring our stress levels daily, stretching, journaling, having hobbies, breathing exercises, talking with a trusted friend at work, laughing, having interests outside of animal welfare, sleeping, allowing yourself to feel grief, dancing, meditating, practicing gratitude and positive thinking, and separating our work life from our personal life.

Regularly doing these acts of self-care builds resilience. People who are resilient are able to bounce back from adversity, stress, and the heartache of getting a dog you loved returned to you abused and broken. It helps you bounce back from euthanizing animals.

Research shows us another key to building resiliency and fighting Compassion Fatigue: experiencing Compassion Satisfaction. All of us who have worked with animals have known Compassion Satisfaction (CS). That’s the joy in our job.

CS happens when you care for an injured animal until they are well again. CS comes from doing a wonderful adoption for a long term resident. CS comes from passing out peanut butter Kongs and listening to a choir of muffled, content slurps. CS is when you help a caring family keep the dog they love by connecting them to affordable resources. CS is what keeps us going, helps us balance out the negative, and see the big picture. But we can’t hold on to the positive aspects of CS without self-care.

If we really want to make progress in animal sheltering, then we have to make teaching and supporting self-care a foundation of our work. Entire organizations can be affected by Compassion Fatigue. And the organization itself can cause stressors for employees that contribute to fatigue and burnout, such as improper management, unclear protocols, lack of training, low pay, being understaffed, etc.

If we want shelter workers to do their best work, organizations and their management have to be aware of these issues and work to help staff and volunteers to identify healthy coping strategies and encourage them to build resiliency. We have to make this non-negotiable and as important as any other part of their training, since neglecting self-care has negative consequences for our work. It has to be a part of the culture of our profession: prioritizing self-care, so we can care for others.

If we want to save more lives, organizations will have to combat the plague of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout that wipes out entire groups of new, enthusiastic, caring, shelter workers before they even have a chance to make a lasting impact for the animals.

As a profession we have to prioritize caring for the caregivers by investing time and resources into this issue. We can’t just expect them to suck it up, stay positive, and do good work. I sure couldn’t. At the end the only way I knew how to help myself was to pick up the pen and write my resignation letter. The day I dropped it off on my mangers desk I knew, even though I felt terrible quitting, it was an act of self-care.

PDF Version for easy printing and sharing available here: Self Care is Not Optional

Despite being way too long, this blog only scratches the surface. For more concrete resources, please see my interview with Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project Founder Patrica Smith.

Compassion Fatigue and Burnout affects professional caregivers of all kinds (as well as those that are caring for loved ones in their personal lives). This includes vet techs, individuals who live with challenging or sick dogs, dog trainers, animal control officers, and volunteers. What I wrote about here applies to all of us who are taking care of animals or people. Self-care is not optional for any of us.

And finally, because this had such an impact on me personally, this summer I became a Certified Compassion Fatigue Educator. 11/2014 note: I now have a whole new website and more compassion fatigue resources here, including online classes and webinars to help you be well, while you do good work.